This is the 17th installment of my weekly poker column in the Economic Times, Range Rover.

“So what is the worst thing you do when you go on tilt?” I asked a couple of my fellow pros the other day. It turned out that all of us had the same answer to that question: we call too much. We become fish when we play at our worst, unable to fold preflop or postflop, falling for hands like lovesick teenagers. And when we’re on our A-game, this is exactly the flaw we exploit in others.

And yet, and yet. I recently read the latest book by one of my favourite poker writers, Ed Miller, Poker’s 1%: The One Big Secret That Keeps Elite Players on Top. Early on in the book, Miller states that most poker players fold too much. He writes: “In today’s game, the vast majority of regular no-limit players have folding frequencies on the turn and river that are too high.” The other big leak that regulars have, he says, is that they don’t bet enough. In other words, they give up on hands too often.

Let me illustrate this. Someone raises from middle position and you call on the button, and it’s a heads-up pot. On the flop villain bets half the pot. How often are you folding here? Note that I haven’t specified either villain’s range or your range, or the cards that came on the flop. What matters is the bet size. By betting half-pot, villain has given himself 2-1 on his bet. In other words, he needs to win the pot right away better than 1 in 3 times to show an immediate profit. If you don’t continue in the hand at least 66% of the time, therefore, you are basically giving money away.

This logic applies all the way to the river. Miller says that in a heads-up pot, given bet sizes of between half to two-thirds of the pot, you need to continue with 70% of your range on each street. If you don’t, you are exploitable, and are burning money. Equally, if you are the aggressor, you need to bet 70% of your range on each street as well, for similar mathematical reasons. (You are exploitable if you bet 70% on the flop but give up, say, half the time on the turn.)

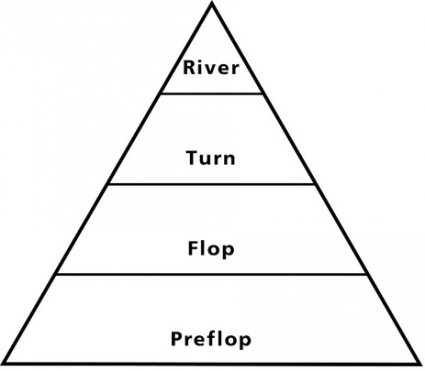

A visual illustration of this rule is the pyramid below. The base is the range of hands you enter a pot with preflop. You discard 30% of it on each street. Miller asserts that the sides of this pyramid should be smooth. Where the pyramid goes out of whack is where a player has a leak. If a player calls too wide preflop and then plays fit or fold, you exploit him on the flop. Some players fold too much on the turn; double-barrel against them. Some preflop agressors give up too often after one c-bet; float against them with any two. And so on. (Note that the pyramid is a guide in heads-up pots, not multiway ones.)

What you need to do to play optimally is to constuct this pyramid for yourself. First, you need to be tight preflop. This way, it will actually be feasable to follow the 70-70-70 rule. For example, if you play 22% of all hands in a full-ring game, by the time you get to the river you will be left with 7.5% (.22 x .7 x .7 x .7), of which 5% will be value and 2.5% will be air. But you will continue with different parts of this preflop range on different flops, such as A33r or QT6 two-tone. You need to construct your ranges accordingly, which takes tons of homework.

Miller’s book is partly inspired by Matthew Janda’s Applications of No-Limit Hold ‘em, and while he lays out what seems to be a framework towards game-theory optimal (GTO) play, as Janda explicitly does, Miller oddly doesn’t mention that term anywhere in the book. The thing with GTO poker is this: even if you don’t intend to play that way, merely understanding what it is can help you identify and exploit other people’s leaks, while eliminating your own. In that context, you might find Miller’s Pyramid to be quite the wonder.

* * *

For more, do check out the Range Rover archives.