This is the first installment on a cricket column I have started for Cricket Next, in which I will write about cricket from the lens of other disciplines, such as economics, psychology, game theory etc.

During his second innings in the Lord’s Test, Virat Kohli could be seen grimacing, and a nation grimaced with him. Kohli has a chronic back problem. The rest of the country has a chronic cricket problem. Why can’t our batsmen play the swinging ball in Test matches in England? Why did this particular lot look so incapable? Why are they worse at this than previous generations? Can an asteroid please give us deliverance by hitting Earth, wiping humanity out and ending this pain?

I am both a Cricket Tragic and an India Tragic, and I will make three tragic arguments in this piece. One, Indian batsmen of the future will be even worse against the swinging ball in England. Two, it doesn’t matter because Test cricket is dying, and there won’t be any Test matches in England 20 years from now. Three, that also doesn’t matter, because cricket will flourish nevertheless, and other forms of the game have as much drama and nuance as Test cricket does, if in different ways.

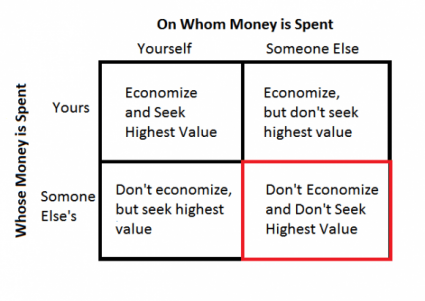

This may sound dismal to you, so its apt that I make my argument through the lens of the allegedly ‘dismal science’ of economics. In particular, I want to look at Incentives: what are the incentives of those who view the game, play the game, and run the game? How is their behaviour moulded by these incentives? What are the implications of this?

First up, consider the concept of Opportunity Cost, which, put simply, refers to what alternative uses you could have made of the time or money you spent on something. The opportunity cost of watching a Test match, for example, is what else you could have done with the five days you spent watching it. This boils down to the options available for your time.

For most of cricket’s existence, there haven’t been that many alternatives. There is a cliché about cricket and Bollywood being the two great 20th century passions of India, but think about it, what else did you have for entertainment? Not much television, and no internet, Facebook, Whatsapp, Youtube, Netflix or easily available porn. That has changed today.

We’re inundated with options of what to do with our time. That means that the opportunity cost of watching a Test match has shot up, and our incentive for doing so has declined. Most cricket purists I know don’t actually spend much time watching Test cricket. (Look up another concept from economics, ‘Revealed Preferences’.) The TV ratings of Test cricket have been plummeting, and if not for the subsidy from other forms of the game, there would already be no commercial reason for the game to exist.

What is remarkable about Test cricket is that it exists at all. Most other popular sports can be viewed in easy-to-digest nuggets. Football lasts 90 minutes, not nine hours. Tennis matches, hockey games, badminton encounters can all be done with within an evening. And because there is no longer form of the game to compare these sports to, no one complains about how they lack drama or depth.

I believe that we complain about Twenty20 cricket because Test matches came first, so we put that on a pedestal, and consider that the basis of comparison. (Another economic concept to look up: the ‘Anchoring Effect’.) Had T20s come first, we might have viewed Test cricket through a different prism of values – and found it wanting.

Use the tools of economics on a T20 game. Each team is given as many resources (11 players) as in a Test or a one-day match, but far less overs (only 20) to play an innings in. This relative scarcity of overs changes the value of all the resources. A dot ball becomes more expensive for the batting side, as every ball carries more value. A wicket has less value than in an ODI, as your batting resources need to be spread out over only 20 overs rather than 50. The risk-reward ratio changes, and the value of aggression goes up.

This changes the incentives for batting sides. Aggression is rewarded, the value of ‘building an innings’ goes down, and to finish an innings with batsmen still waiting in the pavilion counts as a waste of resources. (Opportunity cost, again.) Batsmen, thus, have to innovate far more, and find new ways of playing the game.

Consider the much-touted 360-degree game of AB de Villiers. There, invention came out of necessity, the new format making demands on batsmen to expand their repertoire. ABD is just the most spectacular player around. Many other batsmen started practising new strokes, playing them reflexively, expanding not just their repertoire but also the orthodoxy. Who is to say that the reverse-sweep and the ramp shot don’t now belong in batting textbooks?

Contrary to a popular canard, bowlers did not turn into bowling machines. Their response to more aggressive batsmen was more deception, and not just by bowling more slower balls and wide yorkers. Spinners actually began flighting the ball more, inviting batsmen to hit them, like back in the romanticized days of yore. Think back on the bowling of the spinners like Rashid Khan, Kuldeep Yadav and Yuzvendra Chahal in the last IPL: the flight, the loop, the aggressive intent. Bowlers figured out that one way to counter the momentum of a batting side was to take wickets. Attack became the best defence.

This might seem contradictory. On one hand, the value of a wicket goes down for a batsmen because runs are more important. On the other hand, the value of a wicket goes up for a bowler because it can slow a batting side’s momentum. So how much do wickets matter?

Questions like this make it a fascinating time to be a cricket lover. There is an ongoing conversation between batsmen and bowlers, with both innovating new skills as they test this hypothesis or that. This is why watching the IPL is so eye-opening and mind-boggling. A game is evolving in front of our eyes: its grammar and structure, its mores and norms, through a conversation between batsmen and bowlers and captains that we get to see in real time.

If you love cricket, how can you not be enthralled?

Now consider how the incentives change for everyone concerned. Viewers prefer T20s to Tests because the opportunity cost of watching a T20 game is far less. (Besides, it is an incredibly rich experience, having that added dramatic element of urgency that Tests do not have.) Because of this, there is more money to be made excelling in this shorter form of the game. So players are incentivised to optimise for it. Every minute that a batsman spends expanding his repertoire of aggressive strokes, though, carries the opportunity cost of not practising for Test match skills, such as how to leave a swinging ball.

The inevitable outcome of this is that batsmen will always train to play T20s, and will be unequipped for those specialised skills that Test matches demand. (Especially Test matches in England.) India tours England once every few years. Why should KL Rahul, who I consider a batting genius, spend much time preparing for conditions he will encounter so infrequently?

Another indication of how these incentives play out: only Cheteshwar Pujara bothered to go to England early and prepare for this tour. He did so only because he has been discarded in the other forms of the game. Incentives. Contrast this with the fact that the Indian batsmen of the generation immediately preceding the IPL era, the Dravid-Tendulkar-Ganguly generation, all played county cricket. But why should KL Rahul or Rishabh Pant bother with that?

It is not fair to make a value judgement about this. All these players have made rational choices, responding to incentives. Who is to say that one specific ‘balance between bat and ball’ is better than some other balance? Who is to say that Test cricket is superior to one-day cricket? Even many who do state that as a personal preference don’t actually put their eyeballs where their mouths are.

People who love Test cricket, as I do, can take succour in the fact that the cricket boards will keep the form alive even when it is no longer commercially viable, by subsidising it from income that comes from shorter formats. But for how long will this posturing be necessary? When the 15-year-old of today is 35 years old, who will care for Test cricket? Especially if that kid is an Indian viewer who watched this Lord’s Test and thought to himself, “Ya whatever. Why even bother?”