This is the 30th installment of The Rationalist, my column for the Times of India.

I often write this column sitting at a cafe somewhere, but am doing this particular instalment from the safety of my home. I’m taking Covid-19 seriously, and doing all I can in terms of social distancing, personal hygiene and so on. People tend to underestimate the nature of exponential growth, and I worry that many of my fellow countrymen are still too complacent. But there is an ongoing epidemic I worry about just as much as Covid-19 – it is the epidemic of ignorance that causes people to believe in alternative medicine.

Over the last few weeks, we’ve seen all kinds of dubious assertions about Covid-19. Homeopaths and Ayurvedic practitioners have suggested medications, bovine urine has been offered as a prophylactic, groups of people have chanted ‘Go Corona Go’ to the supposedly obedient virus, and there is even a suggestion that clapping hands drives bacteria away. These alleged remedies, and the belief systems they are based on, are wrong. They are also dangerous, which is why it is necessary to fight them with the same commitment with which we need to fight literal viruses.

To begin with, I have a visceral objection to the term ‘alternative medicine’. Most of the quackery we put in that category is not medicine at all. There are only two kinds of treatment: those that work, and those that don’t. Real medicine on one hand – and quackery on the other. The term ‘alternative medicine’ dignifies quackery, and implies an equivalence that does not exist.

And here you say, but so much of what I call quackery seems to work. Why so? Let me offer two reasons.

The first, as is commonly known, is the placebo effect. Basically, merely believing that a medicine will work can sometimes make the patient better. A classic example of this comes from World War 2, when Henry Beecher, an American anaesthetist, ran out of morphine and was forced to use salt water instead for an operation. The patient did not know this, and the salt water worked. Or rather, the placebo effect worked. (Salt water is not an anaesthetic.)

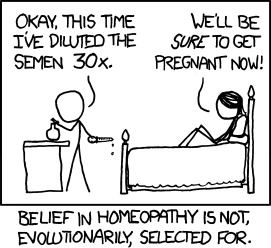

For this reason, when scientific trials are carried out to determine whether a medicine works or not, the standard is not whether the patients get better. Instead, the medicine being tested has to perform better than placebo. This is done through what is called a double-blind placebo-controlled test. Patients are divided into two groups, one of which is given a placebo and the other is given the medication being tested. Neither the patients nor the doctors know which is which. If the medication outperforms the placebo, we know it works. No homeopathic medicine has ever passed such a test.

A second reason for why quackery seems to work is regression to the mean. Many illnesses, like the common cold and some migraines, function in a cycle and get better on their own. Patients often ascribe credit for this to the medication they took. This is especially likely if they already believe in it, in which case the confirmation bias kicks in – the tendency to see only evidence that confirms our biases.

But homeopathy is harmless, right? Only sugar pills? So what is the problem?

There are two problems with using alternative medicines. One, what economists would call the opportunity cost: you are not using medicine that actually works, and that could kill the patient. A famous example of this is the Australian couple who insisted on treating their daughter’s eczema with homeopathy. (The father was a homeopathic ‘doctor’.) The girl died, and the parents were correctly convicted of manslaughter.

Two, people who believe in such treatments can become complacent about the danger they are facing. Watch the viral video of those gentlemen chanting ‘Go Corona Go’, and it is clear that they are standing too close to one another. My favourite app TikTok is full of videos from people claiming that religion, the oldest form of fake news, will protect them. These false beliefs are dangerous not just to them but to others around them as well. (I guess that video might be viral in more than one metaphorical sense.)

Even when the horrors of Covid-19 is behind us, this epidemic of ignorance will continue to take lives. This is especially when the Indian state itself spends taxes coerced from us on this nonsense – the Ministry of AYUSH should be abolished. It is not just believers at risk, but those around them.

What can you do about it, you ask? Well, first, be a skeptic. Examine every assertion, read up on any subject on which you have an opinion. Two great books I recommend on this subject are Bad Science by Ben Goldacre and Trick or Treatment by Simon Singh and Edzard Ernst. Sites like Alt News also do a great job of debunking nonsense. Use them to correct those pesky uncles in your whatsapp groups and housing societies. It is your civic duty to speak up.